Elementos filtrados por fecha: Lunes, 02 Septiembre 2024

The NMWA Clothesline (2018)

Photo: Kevin Allen, National Museum of Women in the Arts

On September 2017, I went to Washington to conduct three workshops to activate El Tendedero at the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA).

The groups, selected by the museum, included House of Ruth (a shelter for battered women), La Clínica del Pueblo (an organization that provides support to migrants), and a group of local artists and activists.

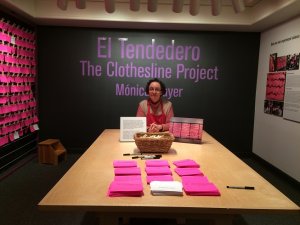

El Tendedero was shown between November 10, 2017 and January 5, 2018, during the height of the #MeToo movement. This was the first time the piece had an exhibition of its own. All the information was bilingual, with cards and instructions provided in both English and Spanish. El Tendedero was displayed on a wall, there was a table in the middle of the room with materials to activate the artwork, and the wall in front showed documentation of past Tendederos and the of the workshops.

I also participated in the museum's public program by giving an inaugural talk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dN5exSPhzPc and was part of a panel discussion with Maurissa Stone Bass (The Living Well) and Dilcia Molina (La Clinica del Pueblo) that was moderated by Melani Douglass, the Director of Public Programs at the museum. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MOj2s7oQ4cQ

Photo: Yuruen Lerma

How did it all begin?

On November 2016, a group of supporters, artists, and associates from the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington had visited my studio in Mexico City and I spoke about my work and gave them a tour of the Pinto mi Raya Archive. One of the visitors was the honorable Mary V. Mochary, a recognized judge and Republican politician who showed a great interest in having the museum acquire El Tendedero. I explained that I felt it would be unethical to profit from women’s pain, so I could not sell it, but if my expenses were covered, I would gladly go to Washington to create a new Tendedero.

The project went ahead, and on September 2017, my daughter Yuruen Lerma and I went to Washington to start it. At the time, the #MeToo movement was unfolding, serving as a backdrop for its presentation in November. Unlike other Tendederos in which I have collaborated with artists and activists, the museum wanted me to work with specific communities they were reaching out to, such as the House of Ruth, a shelter for battered women, and La Clínica del Pueblo, an organization that provides services to migrant communities. The idea was to conduct three workshops: one in each of these organizations and another one with artists and activists. In these workshops, we would define the questions for this Tendedero, and, those who wanted to, would take them to their communities to gather responses.

I accepted because I like each Tendedero to be different, as it allows me to face different contexts and learn from everyone participating, even though I always prefer to work with women who themselves organized the piece or who chose to participate. However, I knew it would be a challenge, so I invited Yuruen to collaborate with me. As a psychologist with master's degree in gender studies, she has extensive experience with diverse groups. What I didn't anticipate was how complex it is to work in a culture as foreign to me as the United States.

Photos Yuruen Lerma

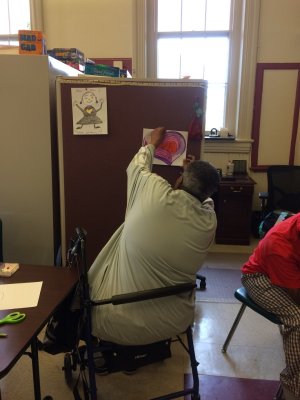

The House of Ruth workshop was difficult for several reasons, among them their specific situation facing violence, but there were also issues of culture, class and race that work very differently in the US and in Mexico and that I simply didn't understand. It took me a while to grasp the dynamics and create the necessary trust for the questions of El Tendedero to emerge from their own concerns. In the end, we succeeded, and one of my favorite questions of all times came from this group: "As a woman, what have you done or would you do to regain joy after being mistreated?" Coming from my culture, joy had never been a goal to reach as part of the struggle against violence. Their question made me change.

Photo: Yuruen Lerma

The group from La Clínica del Pueblo flowed more easily. As soon as we greeted as we do in Mexico with hugs, kisses, and affection, I felt at home.

Participation in the workshop was constant and critical, allowing me to better understand the problems faced by migrant women in terms of gender-based violence, especially in the Trump era. Talking with them made it clear to me that countless women in the US cannot afford to report the violence they endure out of fear of being deported. The laws are supposed to protect them, but they have good reasons not to trust the authorities. In this Tendedero, apart from the answers gathered at La Clínica del Pueblo, we left some blank slips on white paper to visibilize those who are unable to speak up. It was particularly important because, as I mentioned, the NMWA Tendedero was presented at the height of the #MeToo movement, when renowned actresses publicly spoke up against harassment in the entertainment industry, and what these little pieces of paper highlighted was that even reporting harassment is still a matter of privilege. In the workshop, I met Dilcia Molina, in charge of the Gender and Health Program at La Clínica del Pueblo. Fortunately, this wise and admirable woman was strong ally of El Tendedero.

Photos Yuruen Lerma

The last workshop was with artists and activists from Washington and Baltimore. It was not easy either. Racial tensions in Washington were strong, and a couple of intense discussions arose around gentrification that overwhelmed me. Additionally, in that context, I was in a difficult situation because, while I am white, I am also Mexican, and one who, having lived in the U.S. for two years, is painfully aware of the enormous prejudice that exists in the United States against us, in general, in the artworld and even in part of the feminist movement, so it was hard for them to place me. However, I found a great ally in Maurissa Stone Bass, a very loving woman and the director of The Living Well, where they had held their own Tendedero on November 3rd during an event called Baltimore Peace Challenge #HealinCommUNITY, which later became part of the one at the NMWA.

Photos Yuruen Lerma

El Tendedero del NMWA / The NMWA Clothesline II: THE INSTALLATION

Photo Kevin Allen, National Musum of Women in the Arts

El Tendedero del NMWA in Washington was beautiful. It was alone in a room at the entrance of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. The little pink slips of papers and purple letters stood out against the dramatic black wall as a backdrop. In the center, on a prominent high table, were the slips in English and Spanish for the public to fill out, along with the instructions. On the wall to the left was El Tendedero.

Photo Kevin Allen, National Museum of Women in the Arts

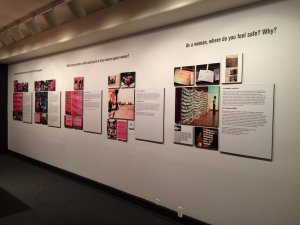

The information from previous Tendederos was displayed on the wall to the right.

Photo Kevin Allen, National Museum of Women in the Arts

The documentation from the workshops, the explanation of the process, the exhibition credits, and acknowledgments of sponsors were placed on a small nook on the left side, at the entrance of the room.

This is the first time that El Tendedero was presented on its own. It had always been part of group shows or my solo shows which included other artworks.

Based on the workshops, we decided to include five questions:

Have you been mistreated because you are a woman? In what way?

Have you reported or would you report mistreatment as a woman? Why?

Where do you feel safe as a woman? Why?

What have you done or could you do against violence towards women?

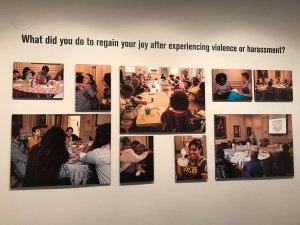

As a woman, what have you done or would you do to regain joy after being mistreated?

Photo Mónica Mayer

I thought the Tendedero would be difficult to fill up, but both the audience and the responses kept flowing. There were many reports of violence against women, but also many answers about personal, educational, legal, and political actions against this sort of violence.

Photo Mónica Mayer

I love to interact with the audience and activate the artwork, so, during the days I was in Washington, I spent my time at the installation in the museum.

It was very interesting. For example, an artist around my age asked me what I do when I'm not working on El Tendedero, and we ended up having a long conversation about the multiple jobs we have to do to survive and support our art work. The situation in the US is not that friendly towards artists as I thought. Many university students also came because their gender studies teachers sent them. I asked them about the prevalence of harassment at their university, and at first, one student said she hadn't noticed any. We continued talking, and I mentioned that I had read that there were many cases of rape during parties or dates among students. She then told me that she doesn't go to parties because the first time she attended one, a group of guys pulled her around, tugging at her pants, so, although nothing else happened, she stopped going. It hadn't occurred to her that this was also harassment. But the ones that touched me the most were two young women who entered, started texting, and then filled out a response about how to regain joy, which they showed me: they had written to Vilma Dulce, a friend of theirs in Algeria whose face was disfigured by the acid thrown at her by a guy. The response, on the photograph below, still makes me cry.

Photo Mónica Mayer

The answers and the documentation of El Tendedero del NMWA remained at the museum and they also digitalized all the answers which can be consulted on line in the exhibition’s webpage. https://nmwa.assetbank-server.com/assetbank-nmwa/images/assetbox/58122d51-7da6-4710-8ac4-07f43530088d/assetbox.html

El Tendedero del NMWA / The NMWA Clothesline III: The Forum

Photo Kevin Allen, National Museum of Women in the Arts

The Public Programs department, directed by Melani Douglass and coordinated by Alicia Gregory, is one of the areas that is gaining increasing relevance at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and my project was one of the first or perhaps the first social practice project at the museum, so we worked closely.

Photo Jennifer Folyanan

The experience was very interesting and I felt the museum truly embraced the project. The museography was splendid, the publicity was top-notch, and the project organization came from a solid and committed team effort. I would like to illustrate this with the last component of the project: the Fresh Talk Forum held on November 12, 2017.

The forum program included a brief lecture I gave about El Tendedero and a panel moderated by Douglass in which Dilcia Molina from La Clínica del Pueblo, Maruissa Stone Bass from The Living Well, and I participated. In the end, it was opened to the public, and we concluded with a dinner attended by approximately 200 people who were in the auditorium.

You can find my talk here and the panel here. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL1boWZ4URBmqUMI1MufoGJ6YTMkd2YpAS

Photo Kevin Allen, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Before we started, Melani asked the audience who knew me or my work, and only a couple of people raised their hands. To me, this meant the museum had done a great job inviting people. But I realized it was more than that when, at the end of the panel the moderator, instead of inviting the audience to ask questions, asked them to share their own strategies and actions against violence against women. The entire audience consisted of people dedicated to working on gender issues who came from academia, anti-violence organizations, and artist collectives working on these issues. They had actually handpicked their large audience, laying the grounds for a real conversation and strengthening networks.

However, what I remember the most were the words of a woman born in Guadalajara, Mexico, living legally I the United States, who mentioned that she had recently been forced to explain to her elementary school children the meaning of the word rapist because other kids at school had told them that if they were Mexican, they were rapists. Between gender-based violence and racism (among other forms of oppression), we are living in difficult times.

Photo Kevin Allen, National Museum of Women in the Arts

That night, during the dinner at the splendid museum, any doubts I had about the results of the workshop at The House of Ruth disappeared. Several women from the House attended the forum and participated enthusiastically. Most of them had never been to a museum before. They greeted me warmly, and it was evident that they were having a good time. A large contingent from La Clínica del Pueblo also arrived. One of them mentioned that many migrants didn't even go near that part of the city because there were many government buildings, or they thought they would be asked for an ID at the entrance of the museum, and they were afraid of being caught. I saw only a few of the artists and activists from the last workshop. Interestingly, that was the least successful meeting.

Something that pleasantly impressed me about the NMWA Tendedero was the project's presence in the media, with articles in newspapers such as The Washington Post and The Guardian, among many others. I don't know if the project caught their attention, if the museum's press department does an excellent job, if covering Mexican projects is a form of resistance against Trump, or if the presence of the #MeToo movement helped to turn the spotlight towards the piece, but the coverage was very good.

Undoubtedly, I was pleased with all this attention to my work, but I thought it was important because until very recently, the history of feminist art has come mostly from the United States and Europe. Little by little, we have to change that narrative.

These are the links to some of the articles.

Turning a Clothesline into a Powerful Feminist Statement by Mallory Nezam. Hyperallergic, January 3, 2018.

Before #MeToo, There Was El Tendedero by Kristin Kirsch Feldkamp. She files, December 31, 2017.

Interactive exhibition invites visitors to leave comments about sexual abuse and harassment. Art Daily. December, 2017

Rows Of Hot Pink Paper, All Saying #MeToo by Greta Jochem, Goats and Soda, December 10, 2017.

#MeToo, the analog way: Survivors tell their stories with ‘The Clothesline Project’ by Jessica M. Goldstein. Think Progress, December 4, 2017.

The Clothesline Project: an Exhibit Asking to Share Stories of Sexual Abuse by Nadja Saye. The Guardian, November 16, 2017.

Timely Art Installation Attracts #MeToo Audience por Susan Focher Sterling. The Huffington Post, November 14, 2017.

Art installation on sexual harassment and violence opens at Museum of Women in the Arts by Peggy McGlone. Washington Post, Arts and Entertainment. November 13, 2017.