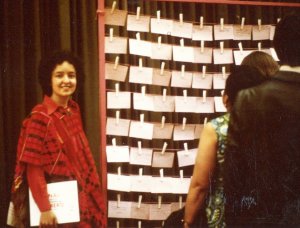

El Tendedero was first shown during the Salón 77- 78: Nuevas Tendencias exhibition on March 22, 1978, at the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City.

Photo: Víctor Lerma

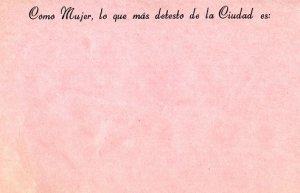

The piece consisted on asking women from different social classes, ages, and professions to respond anonymously on small pink slips of paper to the question: "As a woman, what I detest the most of the city is...". Their answers were then hung on a two by three-meter structure at the museum.

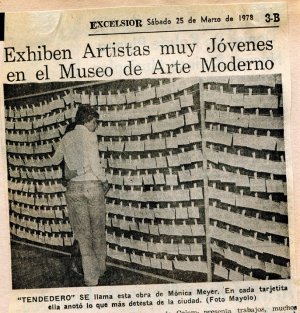

Photo: Víctor Lerma

When I started gathering the answers, many women mentioned pollution and traffic as the main problems. I would then ask them if anyone had ever felt them up or if they had received cats in the public transport. They invariably said yes and I would then invite them to share that experience. At the time we didn’t even have the vocabulary for different types of violence against women such as harassment, and most of us had never spoken to anyone about them. Although in the end some women referred to other problems, most responses referred to sexual violence in public transportation. Something curious happened at the museum: women who visited the exhibition spontaneously joined in and wrote their own answers on any available space in the front or back of the slips. They made it their own. The piece also resonated in newspapers.

This work was important for me because, although the content of my other works was already feminist, it was the first time I experimented with participatory art, and things for which we didn’t even have a name for at the time, such as artivism or social practice.

On the other hand, El Tendedero clearly showed that harassment was not something experienced individually, but part of a social structure. It also made women feel it was a safe space where they could share their experiences, read what other women went through and understand that we were not alone. For me, it was a physical manifestation of the consciousness raising groups that were so important in the sixties and seventies, where we each had the same space to share our experience, where we learned both to listen and to speak up.

Today, El Tendedero has also been presented in Europe, North, Central and South America, India and Japan at museums, biennales, performance festivals, at universities and at a grassroots level with artists and feminist groups. It has also been widely activated all over Mexico. Early on it became a collaborative piece where I facilitate a workshop for groups interested in organizing one, where I would share information about the different problems and specific contributions faced in different iterations, and the participants define the questions for their Tendedero and strategies on how to present it. The themes dealt with in each of them have become more varied, leading to Tendederos about violence against women in the church, female nurses or women in non-government organizations. There was even one where women spoke up against the problems they face when they try to denounce violence against women legally. Today, for me, the piece is the story of all the different Tendederos.

However, the most important thing about the El Tendedero is that it has become a feminist activist methodology, it gone viral, become part of the popular culture, and many groups of women, often students, use their own version in which, unlike mine, they denounce their aggressors. My Tendederos have always been anonymous, mentioning neither the name of the woman who writes or her aggressor. I did them like this because their purpose was to change the narratives that uphold the patriarchy. In these new versions, influenced by the “Escrache” movement in Argentina, Anarchist Direct Action and the #MeToo movement, they are used as a tool to denounce. Today, when I start a workshop, I often invite young women who had previously done their own Tendedero de Denuncia, and their experience has allowed me to learn about how they have succeeded in changing their schools or the backlash they have suffered, so that in future groups, I can share how they can take care of themselves and also how to make the most of the invaluable information collected in each Tendedero, since women have used it in many different ways.

In this space, I will share the stories of seven iterations of El Tendedero in the United States. It is an effort to start sharing information in English on the piece so that it reaches broader audiences, but I also think they are important examples of how it has worked in different contexts over several decades.